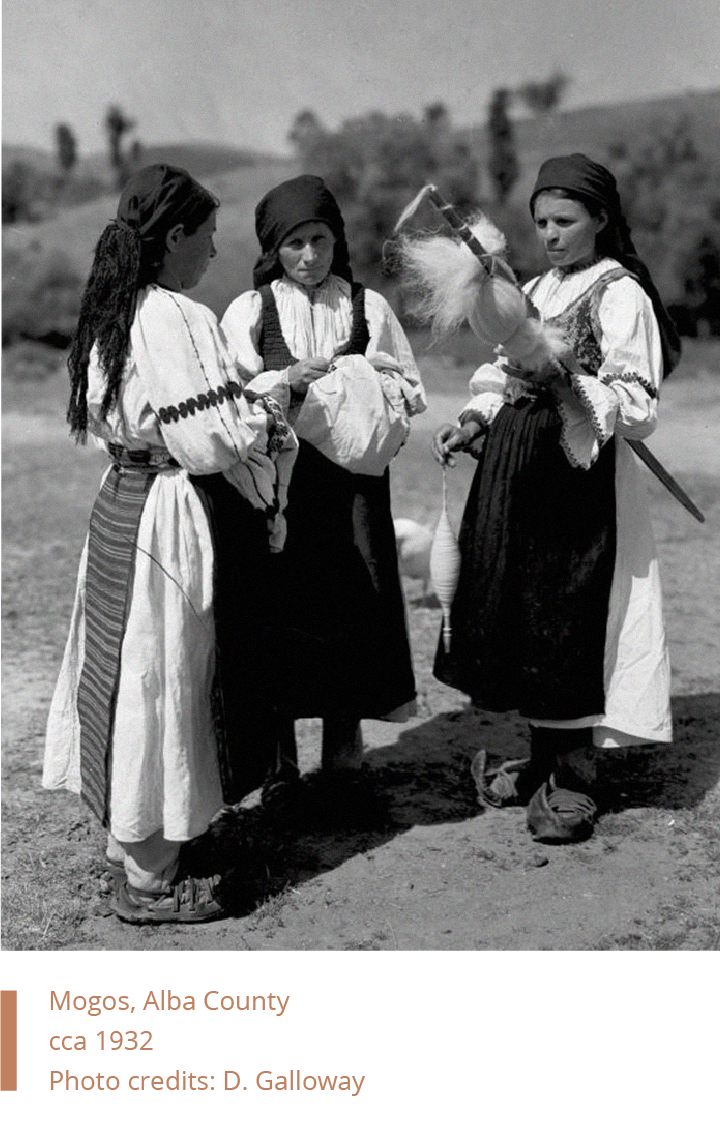

Intrinsic part of the villages everyday activity, closely tied to the calendar of local happenings — the making of garments is social at all times. The creation of folk clothing would spread over the time span of a whole year as it implied the making from scratch of the hemp and linen fabrics as well as of the wool cloths and natural dyes, culminating with the complex hand embroidery stage.

NATURAL FIBERS: textile fibers

Raw materials were used at all times. The fabrics were either made from vegetable fibers, from the stalks of hemp (cânepă), flax (linen — in), the seeds of cotton (bumbac), from animal fibers: wool (lână) or natural protein fibers: silk (borangic). All households would have hemp plantations, as the making of hemp fabrics represented a quintessential aspect of village life.

Initially, all dyes were natural and handmade within the household — however, after WWI, synthetic dyes started being introduced, which brought about the embrace of new colours.

The most common natural dyes made out of plants included:

— Red and black, derived from the bark of the Mountain Alder — Alcus Incana. Red was also obtained from the leaves of dogwood (Cornus) or from the leaves of garance (madder tree, Rubia Tinctorum) in Oltenia.

— Shades of brown: from the bark and leaves of the walnut tree (Juglans Regia).

— Soft grey from danewort (Sambucus ebulus)

— Yellow from the leaves of sorrel (măcriş or ştevie) or the leaves of onions.

Initially, all dyes were natural and handmade within the household — however, after WWI, synthetic dyes started being introduced, which brought about the embrace of new colours.

The most common natural dyes made out of plants included:

— Red and black, derived from the bark of the Mountain Alder — Alcus Incana. Red was also obtained from the leaves of dogwood (Cornus) or from the leaves of garance (madder tree, Rubia Tinctorum) in Oltenia.

— Shades of brown: from the bark and leaves of the walnut tree (Juglans Regia).

— Soft grey from danewort (Sambucus ebulus)

— Yellow from the leaves of sorrel (măcriş or ştevie) or the leaves of onions.

The Tools

The making of the tools necessary in the processes of retting, scutching, combing, spinning and weaving of the natural fibers was an intrinsic part of the village’s everyday life, meant to culminate in not only functional items but works of art in themselves.

The tools involved in the process of fabric making are: meliță (swingle), raghilă, hecelă, or darac (the heckling combs), furcă (distaff), fusul de tors (spindle) and războiul de tesut (loom). The process of cloth-making was a woman’s occupation, but the making of the instruments and apparatuses was the work of men: shepherds — fathers, brothers or bachelors alike — would carve beautiful wooden furci — distaffs, and fusuri de tors — spindles, for the ones they loved, usually during the long and lonely transhumance processes of herding sheep from higher pastures during summer to lower ones during winter. The more complex the carvings, the bigger the love confessions.

The tools involved in the process of fabric making are: meliță (swingle), raghilă, hecelă, or darac (the heckling combs), furcă (distaff), fusul de tors (spindle) and războiul de tesut (loom). The process of cloth-making was a woman’s occupation, but the making of the instruments and apparatuses was the work of men: shepherds — fathers, brothers or bachelors alike — would carve beautiful wooden furci — distaffs, and fusuri de tors — spindles, for the ones they loved, usually during the long and lonely transhumance processes of herding sheep from higher pastures during summer to lower ones during winter. The more complex the carvings, the bigger the love confessions.

THE PROCESS OF FABRIC MAKING

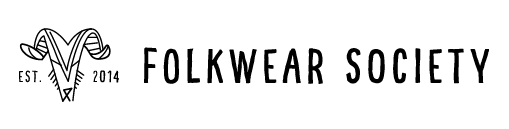

RETTING

During summertime, the process of retting would begin. Topitul cânepii — literally, the melting of the hemp, refers to the retting stage that implies soaking the flax or hemp in water to soften them. Bundles of stalks of hemp and flax are submerged under the water of rivers or in specially designed water basins set up in the village. The bundles are weighted down with stones and wood to prevent them being carried away by torrents. Retting time is very important: what happens during the retting process is that water, by increasing absorption of decay-producing bacteria, dissolves away much of the cellular tissues around the bast-fibers (such as hemp and flax), thus separating the fiber from the stem. After roughly two weeks of retting, they are left to dry in open air.

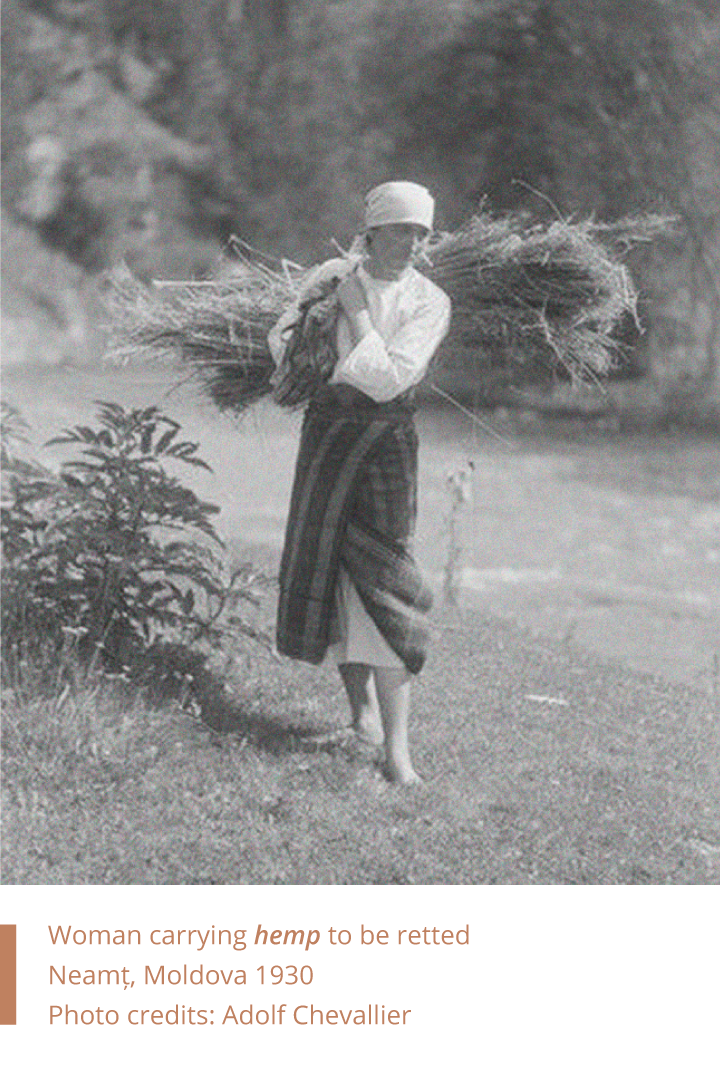

SCUTCHING

During autumn, the noise of battering the dried fibers with an instrument called meliță (swingle) resonates in the whole village. This is part of the process of scutching: dressing fibers by beating them and sorting the hemp (or flax) from the remnants of the wood fiber — puzderii (the shives).

COMBING

Next stage is grooming time! The long hemp and flax fibers as well as the coarser fibers called tow are then combed with large combs called raghilă, hecelă, darac (heckling combs or heckles) — they weed out further unwanted bits, resulting into finer threads (yarns), ready to be spun. This process is repeated two or three times until the longest and finest and softest fibers become what’s known as “fuior”.

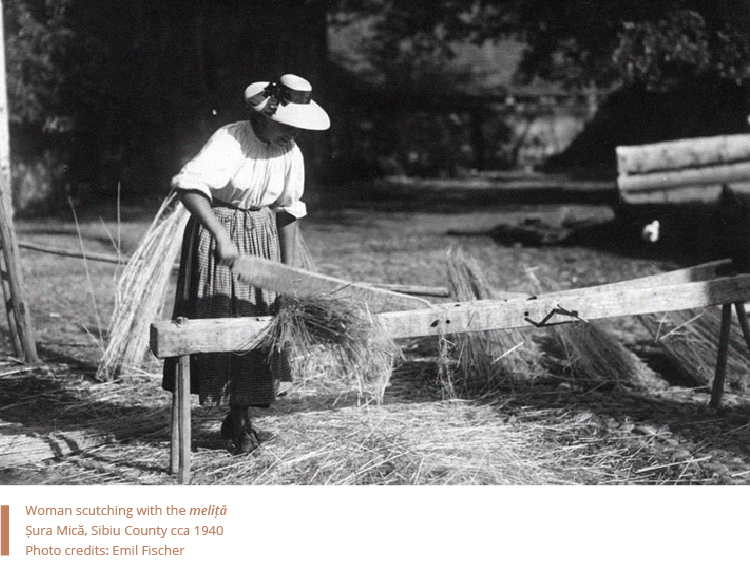

Spinning

The action of spinning is literally translated to “purring” (in Romanian, tors — a toarce). This is where the distaff and spindle come into play. The result of the spinning process is the conversion of the natural fibers into yarn. During this lengthy stage, women would gather at “clăci” — a sort of spinning and gossiping get-togethers.

Spinning would be so important that a myth existed addressing “lazy” girls: “Joimărița”, an old witch, come spring, would storm by women’s houses and inspect every inch in the search for hidden unspun tow, punishing those lazy ones by kidnapping them or burning their fingers.

Spinning would be so important that a myth existed addressing “lazy” girls: “Joimărița”, an old witch, come spring, would storm by women’s houses and inspect every inch in the search for hidden unspun tow, punishing those lazy ones by kidnapping them or burning their fingers.

WEAVING

The spun and dyed fibers are then prepared to be weaved on the loom — război de tesut. A notable weaving process is alesătură and neveditură — decoration technique that consists in introducing, by hand, the coloured yarn between the warp and weft.

Wool

SHEEP SHEARING

Tunsul, the trimming of the sheep. Process that happens especially in traditionally pastoral areas such as Mărginimea Sibiului, southern Transylvania — the action of shearing normally takes place during the first months of warmer seasons, mid spring to early summer.

SKIRTING

A transitional stage of trimming the fleece before washing it. It’s not uncommon for less than half of the initially collected wool to “survive” the skirting process.

SCOURING

Spălatul, this is the washing process by which the fleece is submerged into the waters of the nearby rivers. Thus, grease, mud, thorns and other vegetable matter are separated from the raw wool. Afterwards, wool is rinsed and left to dry

Combing

Referred to in Romanian as scărmănatul lânii and dărăcire. This stage, carried out by hand and with the help of heckles or cheptănuşi, involved disposing of remaining vegetable matters and shorter fibers, thus classifying the resultant wool threads into păr (longer threads) and canură (shorter and thicker threads).

Spinning

SEWING AND EMBROIDERY

After sewing the resultant rectangular folds of fabric together, adding the gussets and dying of the fabric (in the case of the colourful woolen catrințe — aprons), the final stage of embroidery embellishment unfolds. Girls learn how to sew and embroider from a young age.