Below is a very brief overview of the historical and ethnical background of Romania, as an aid to better understanding the complex social, political and cultural dynamics playing out behind every item of Romanian folkwear.

History

Romania wasn’t always the Romania mapped out today. The nation itself was only officially established in 1918 – the year that all three principalities, Wallachia, Moldova and Transylvania came together. The tribulations of WWII brought further changes by severing the territories east of the Prut river (today the Republic of Moldova) and northern Bessarabia, thus giving the current national contour of Romania.

Previously, the two vassal principalities, Wallachia and Moldova, had merged under one ruler in 1859, officially started bearing the name of Romania in 1862, with Romania becoming a Principality under King Carol I in 1866. In 1877, Romania gained independence as a result of the Russo-Turkish War, officially proclaiming independence from the Ottoman Empire. Four years later, Romania became a kingdom (constitutional monarchy) and enjoyed decades of stability and progress up to the interwar period. In 1947, King Mihai I was ousted from power and what followed was half a century of communist rule. After the 1989 Revolution, Romania parted with the communist past and in 2007 became a member of the European Union.

Romania has, until the second half of the 19th century, found itself struggling at the crossroads between the Hungarian Kingdom - thence, the Habsburg Empire – in the case of Transylvania and the Ottoman Empire in the case of Wallachia and Moldova. This brought a mélange of ethnic cultures together on the same territories: German and Hungarian in Transylvania, and Turkish, Greek and Macedonian in Wallachia and Moldova. Although Romania has always consisted of a large majority of ethnic Romanians, the ethnic minorities that settled over the centuries have all influenced the social, economic and ethnographic landscape.

Previously, the two vassal principalities, Wallachia and Moldova, had merged under one ruler in 1859, officially started bearing the name of Romania in 1862, with Romania becoming a Principality under King Carol I in 1866. In 1877, Romania gained independence as a result of the Russo-Turkish War, officially proclaiming independence from the Ottoman Empire. Four years later, Romania became a kingdom (constitutional monarchy) and enjoyed decades of stability and progress up to the interwar period. In 1947, King Mihai I was ousted from power and what followed was half a century of communist rule. After the 1989 Revolution, Romania parted with the communist past and in 2007 became a member of the European Union.

Romania has, until the second half of the 19th century, found itself struggling at the crossroads between the Hungarian Kingdom - thence, the Habsburg Empire – in the case of Transylvania and the Ottoman Empire in the case of Wallachia and Moldova. This brought a mélange of ethnic cultures together on the same territories: German and Hungarian in Transylvania, and Turkish, Greek and Macedonian in Wallachia and Moldova. Although Romania has always consisted of a large majority of ethnic Romanians, the ethnic minorities that settled over the centuries have all influenced the social, economic and ethnographic landscape.

Cultural & Ethnic mix

Transylvania was a particularly interesting place of struggles and tensions. The Habsburg rule established in the 17th century excluded Romanians from the political life on the basis of their religion. Since Roman Catholicism was the sole religion to be recognised, the only acknowledged nationalities in Transylvania were the Hungarians (Magyar and Székely) and the Germans (Saxons). The contestations between the ethnic groups of Romanians and Hungarians which followed this tumultuous period, have made Transylvania a major locus of interest for studies on nationalist politics. In fact, several scholars argue that the 19th century wave of ethnic nationalism ignited in the Romanian principalities was rooted in Transylvania.

Here are some of the most relevant ethnic minorities, who, despite having migrated from regions far away, have nonetheless preserved their individual ethnic folk clothing and also allowed for subtle exchanges and influences to and from Romanian folkwear.

Here are some of the most relevant ethnic minorities, who, despite having migrated from regions far away, have nonetheless preserved their individual ethnic folk clothing and also allowed for subtle exchanges and influences to and from Romanian folkwear.

Secui (Székelys)

Secui (Székelys) are of Hungarian origin and settled in Transylvania between the 9th to the 12th century. Today, there are still a few counties predominantly Hungarian-ethnic, such as Harghita and Covasna, in central Transylvania.

The Hungarian folk clothing slowly transformed after the First World War – as the household production of fabrics declined amongst Hungarian villages, the new industrially available fabrics started changing the tailoring and the ornamentation of the folk outfits, making them more in touch with the urban fashion.

The Hungarian folk clothing slowly transformed after the First World War – as the household production of fabrics declined amongst Hungarian villages, the new industrially available fabrics started changing the tailoring and the ornamentation of the folk outfits, making them more in touch with the urban fashion.

Sași (Saxons)

The German-ethnic saxons (sași) were colonized on Transylvanian grounds around the 12th century. They developed as a unitary social, economic and political entity with its own cultural, linguistic, visual and material expressions and full political autonomy by 1876. The sasi settled mostly in the Sibiu area of southern Transylvania (Sibiu, Medias, Sighisoara, Rupea), Sebesul Sasesc, Orastie, and further up north around Bistrita and Reghinul Sasesc. Most of the sași left Romania during the last years of communism and after 1989, but left behind a significant folk heritage.

Romani/Roma

(in Romanian, the colloquial țigani is growingly considered pejorative and is being replaced with ‘romi’)

The historical documentation of the Roma population in Romania is difficult as they are intrinsically “un-established” as a community. The third largest minority in Romania after the Hungarians, – the most recent census of 2011 registered 3.3% of the Romanian population identified as Roma – they are also the most economically and socially disadvantaged. Until mid 19th century they had been deprived of many rights and locked in slavery. During the Second World War, tens of thousands of Roma were deported to Transnistria and more than 38.000 have died in that period of time.

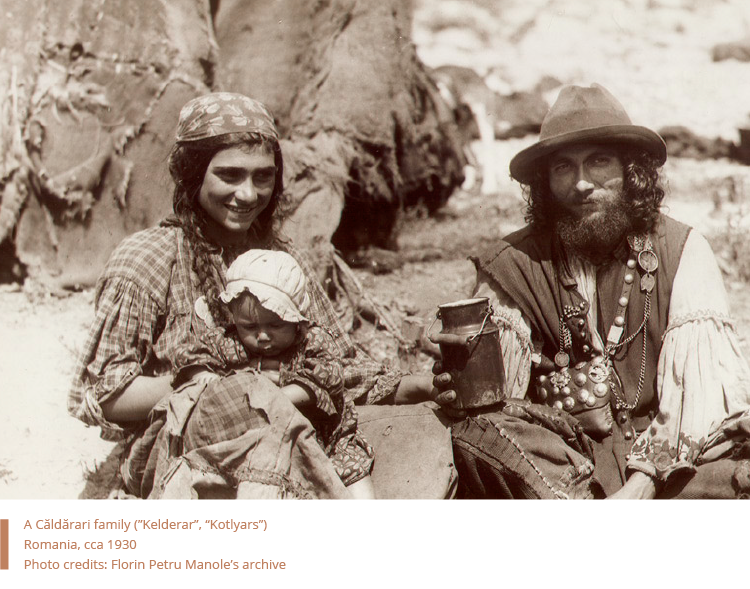

There are several Roma communities who distinguish themselves by their traditional trades: Lăutari (musicians and dancers), Căldărari (Kelderer, Kalderash, tin and coppersmiths), Fierari (Blacksmiths), Lingurari (Spooners).

The Romani folkwear is particularly vivid: the traditional dress for women is brightly coloured and made out of a loose blouse, with a full ankle length pleated skirt and apron tied at the waist. Headscarves are mandatory for married women. The Roma hold strict customs around cleanliness: an interesting fact is that all upper body clothing is washed separately from lower body clothing – as the lower body covering is considered polluted.

The historical documentation of the Roma population in Romania is difficult as they are intrinsically “un-established” as a community. The third largest minority in Romania after the Hungarians, – the most recent census of 2011 registered 3.3% of the Romanian population identified as Roma – they are also the most economically and socially disadvantaged. Until mid 19th century they had been deprived of many rights and locked in slavery. During the Second World War, tens of thousands of Roma were deported to Transnistria and more than 38.000 have died in that period of time.

There are several Roma communities who distinguish themselves by their traditional trades: Lăutari (musicians and dancers), Căldărari (Kelderer, Kalderash, tin and coppersmiths), Fierari (Blacksmiths), Lingurari (Spooners).

The Romani folkwear is particularly vivid: the traditional dress for women is brightly coloured and made out of a loose blouse, with a full ankle length pleated skirt and apron tied at the waist. Headscarves are mandatory for married women. The Roma hold strict customs around cleanliness: an interesting fact is that all upper body clothing is washed separately from lower body clothing – as the lower body covering is considered polluted.

The Romanian Peasant of the 19th century and Romanian autochthonist nationalism

The process of Romanian nation building directed its gaze towards the Romanian peasant and the aesthetic virtues of the Romanian peasants' material and immaterial culture. This incessant introspection started with the romantic nationalism of the 19th century and developed to such an extent that the peasant became the very symbol of Romanian nationalist autochthony. A consequence of the ethnic struggle under foreign empires, the emphasis on the Romanian peasant became a political statement: to prove the ancient origin of the “Rumanians” and to justify the right to fight for autonomy.

The discourse on folk art, as such, became one of “continuity and unity” – a tactic of political survival working towards a necessary autochtonist ideology (Hedesan & Mihailescu, 2006). The “Peasant” thus almost lost its cultural and social dimensions and became an ideological actor. Folklorists turned their gaze towards recreating an ancient past, allowing less focus to the subtle cultural changes that occurred within material cultures and rather focused on similarities that revealed the “true origin” of Romanians as the “true” descendants of ancient civilisation of Dacians, people related to the Thracians. By holding on to the ideology of continuity and unity, folklorists sought to discover what they wanted to prove, which resulted in a conceptual – and ideological – Romanian Peasant. Folklore became a medium to a built-up national culture - and omitted the exploration and understanding of the “living peasant”, of the social and performative folklore practice, structure and material culture. Romanian folklore was initially approached from a very positivist mindset of systemic arrangements and collections and typologies.

The discourse on folk art, as such, became one of “continuity and unity” – a tactic of political survival working towards a necessary autochtonist ideology (Hedesan & Mihailescu, 2006). The “Peasant” thus almost lost its cultural and social dimensions and became an ideological actor. Folklorists turned their gaze towards recreating an ancient past, allowing less focus to the subtle cultural changes that occurred within material cultures and rather focused on similarities that revealed the “true origin” of Romanians as the “true” descendants of ancient civilisation of Dacians, people related to the Thracians. By holding on to the ideology of continuity and unity, folklorists sought to discover what they wanted to prove, which resulted in a conceptual – and ideological – Romanian Peasant. Folklore became a medium to a built-up national culture - and omitted the exploration and understanding of the “living peasant”, of the social and performative folklore practice, structure and material culture. Romanian folklore was initially approached from a very positivist mindset of systemic arrangements and collections and typologies.

The Romanian Peasant during communism

In the 1930s, Dimitrie Gusti (one of Romania’s first and most iconic social anthropologists) inaugurated the Village Museum in the capital of Romania, Bucharest. It was a brave move, but in 1948, shortly after the ascent to power of the Romanian Communist Party, the Gusti School of Sociology was decisively marginalised. There was a revival in the mid 1960s – but in 1974, together with the sudden demise of then leading voice in Romanian Sociology, Miron Constantinescu, came the total dissolution of the Sociology department within the University of Bucharest. In 1977, independent sociology departments were dissolved into the History and Philosophy School.

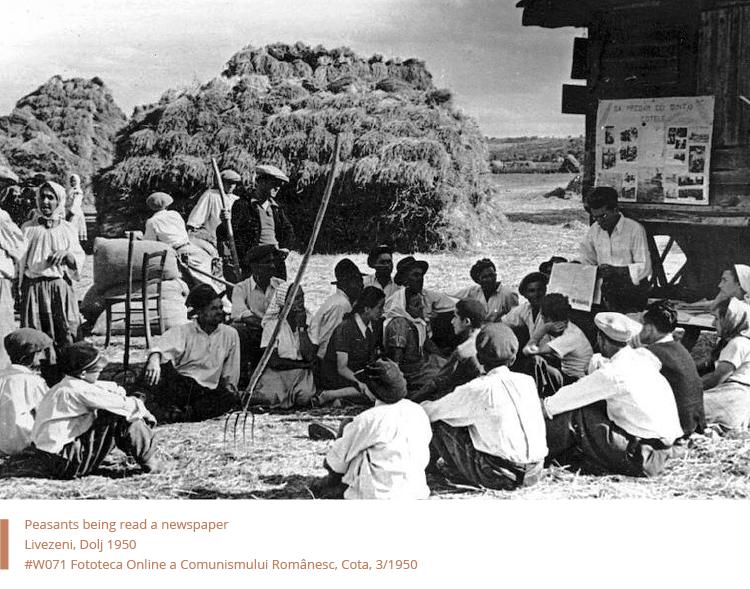

To the communist regime installed, Romania’s rural population – then amounting to 75% of its total population – was considered a great liability to the new order’s modernisation strategies and aspirations. Considered backward and not befitting of a political regime that was heading towards the implementation of a nationalist-communist ideology – peasants were forced into the socio-economic process of collectivisation, a process of forced industrialisation by which they would lose their land and livestock and be coerced into joining the local socialist collective farms that would allegedly optimise the agricultural production of the nation. Peasantry was not only the target of forced modernisation but was also subjected to the imposition of the communist framework of “class struggle”, whereby rich peasants (“chiaburi”) became the villains that ought to be eliminated.

The process of collectivisation extended over a time span of more than 20 years and its social, cultural, political and economic implications are still unresolved long after 1989. Statistics reveal that by 1952, more than 80.000 peasants were incarcerated for refusing to take part, and tens of thousands more were deported hundreds of miles away for resisting. Violent upheavals were not uncommon. The implications of collectivisation included population transfers and forced mixtures between communities.

Ironically, during this time, the “traditional costume” (costumul tradițional românesc) was employed as a vessel of nationalist propaganda and it was omnipresent during communist festivities.

The process of collectivisation extended over a time span of more than 20 years and its social, cultural, political and economic implications are still unresolved long after 1989. Statistics reveal that by 1952, more than 80.000 peasants were incarcerated for refusing to take part, and tens of thousands more were deported hundreds of miles away for resisting. Violent upheavals were not uncommon. The implications of collectivisation included population transfers and forced mixtures between communities.

Ironically, during this time, the “traditional costume” (costumul tradițional românesc) was employed as a vessel of nationalist propaganda and it was omnipresent during communist festivities.

Current Status

Over the past decade there has been a revival of interest in Romanian folk wear. Most notably, the raising interest has prompted the commercialization of contemporary replicas of the Romanian folk blouse (ia). These are, occasionally, handmade replicas, but are most often industrially produced ‘ia românească’, that have little to nothing in common with the original Romanian folkwear. This contributes to a homogenising process, resulting in the loss of the richness inherent in the original items of folkwear. This loss is all the more dramatic given the fact that the originals have not been properly recorded over time.

Given Romania’s slow process of industrialisation, the rural population has perpetuated well into the 20th century – and still makes up half of Romania’s entire population. Peasants have continued to hand make and wear original folkwear that has been passed on to them from generation to generation until the second half of the 20th century and as a result, there are still so many folk garments to be discovered and preserved.

Given Romania’s slow process of industrialisation, the rural population has perpetuated well into the 20th century – and still makes up half of Romania’s entire population. Peasants have continued to hand make and wear original folkwear that has been passed on to them from generation to generation until the second half of the 20th century and as a result, there are still so many folk garments to be discovered and preserved.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bancroft, A. (2005) Roma and Gypsy-Travellers in Europe: Modernity, Race, Space and Exclusion, Avebury: Ashgate Press.

Brubacker, R. (2006) Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Dobrincu, D., Iordachi, C. (2009) Transforming Peasants, Property and Power: The Collectivization of Agriculture in Romania, 1949-1962. Central European University Press

Verdery, K. (1983) Transylvanian villagers : three centuries of political, economic, and ethnic change. Berkeley: University of California Press

Verdery, K. (1996) What Was Socialism and What Comes Next? Princeton: Princeton University Press

Verdery, K. (1985), The unmaking of an ethnic collectivity: Transylvania's Germans. American Ethnologist, 12: 62–83

Kligman, G. and Verdery, K. (2011) Peasants Under Siege: The Collectivization of Romanian Agriculture, 1949-1962. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Burawoy, M. Verdery, K. (eds.) (1999) Uncertain Transition: Ethnographies of Change in the Postsocialist World, Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield

Bancroft, A. (2005) Roma and Gypsy-Travellers in Europe: Modernity, Race, Space and Exclusion, Avebury: Ashgate Press.

Brubacker, R. (2006) Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Dobrincu, D., Iordachi, C. (2009) Transforming Peasants, Property and Power: The Collectivization of Agriculture in Romania, 1949-1962. Central European University Press

Verdery, K. (1983) Transylvanian villagers : three centuries of political, economic, and ethnic change. Berkeley: University of California Press

Verdery, K. (1996) What Was Socialism and What Comes Next? Princeton: Princeton University Press

Verdery, K. (1985), The unmaking of an ethnic collectivity: Transylvania's Germans. American Ethnologist, 12: 62–83

Kligman, G. and Verdery, K. (2011) Peasants Under Siege: The Collectivization of Romanian Agriculture, 1949-1962. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Burawoy, M. Verdery, K. (eds.) (1999) Uncertain Transition: Ethnographies of Change in the Postsocialist World, Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield